Editor’s Note: The following story contains mentions of human remains and loss of life.

Human life might be fragile, but our bodies are surprisingly durable. Thus, many cultures have preserved and displayed human remains; think of Ancient Egyptian or Andean mummified bodies, Tibetan ritual implements made from skulls or thighbones, and the many bits of Catholic saints enshrined in reliquaries. This wide variety of practices is evidence that we humans have likely always been intrigued or shocked by how other communities treat their dead.

The longevity of bodies and our fascination with their treatment means that human remains have often been sold in the times and places when cultures rub up against each other. For example, Torres Strait islander communities collected the skulls of enemies and sometimes sold parts of these trophies to men from Papua New Guinea in the 19th and 20th centuries. One of these sellers rather disdainfully reported to an anthropologist in 1935 that the purchasers then “made big talk,” claiming it was they who had been the killers.

Historians have increasingly investigated the explosive growth of the commerce in exoticized human remains during the colonial era. But what happened when the internet, with its unprecedented acceleration of cultural exchange and global commerce, enters the equation? Damien Huffer and Shawn Graham have summarized their years-long research into this question in their new book, These Were People Once: The Online Trade in Human Remains, and Why It Matters (Berghahn Books, 2023).

Huffer, a forensic anthropologist and criminologist, and Graham, an archaeologist and historian, have spent years monitoring online sales of human remains. To do so, they developed ethical protocols and digital toolkits available in the book’s appendices for collecting and analyzing information from a shifting array of e-commerce sites and social media platforms. The resulting book is their attempt to answer three key questions about the online trade in human remains: “how the trade works, why people do it, and where the people bought and sold might have come from.”

Human remains had been offered for sale on eBay since at least the early 2000s. After the site banned such listings in 2016, sellers soon found other, less regulated e-commerce sites. They also began to post photographs of remains on social media, using backchannel chats and payment apps to complete sales.

Huffer and Graham point to the algorithms governing social media as prime drivers of the exponential growth in human remains sales over the past decade. You might be horrified to see a skull with a price tag on Instagram, TikTok, or Facebook, but a crying-emoji reaction or scolding comment will register as engagement as much as a heart or a compliment. The platform, the authors explain, takes all engagement, whether positive or negative, as a signal to show the post to more and more users.

Huffer and Graham describe the wide-ranging fates of such remains. A surprising number become the basis for morbid craft projects: “We have seen chandeliers, clocks, and once, a skull modified to look like that of a Klingon.” They quote a post from a vendor who claims that their rings, adorned with a “hand-carved piece of skull in the shape of a Ouija planchette,” are perfect last-minute Christmas gifts. One heavy metal musician even plays a guitar made from a human rib cage and spinal column. The dead who are sold online are no longer people. They have been turned into commodities for the sake of “a transgression against ‘normie’ culture, and for profit.”

Throughout their research, Huffer and Graham also used neural networks to look at backgrounds and associated objects in photographs in sales listings. Finding that human remains are often accompanied by taxidermized animals and weapons, they propose that all these artifacts are considered “somehow dangerous” or “exotic” and thus give the person who can own, touch, and display them “a forbidden thrill.”

Remains are often also displayed in wooden cases, cushioned in dark velvet and lit with wax candles (the dribblier the better). Huffer and Graham note that this aesthetic echoes that of a Victorian ethnographic museum. They think it no accident that this style emerged in an era of pushback against the deeply racist ideals first formulated in such museums.

In the last few decades, museums have radically reimagined their displays of human remains (or have entirely removed them from view). Huffer and Graham draw our attention to the creation of “Do-It-Yourself-museums” by current collectors and dealers of human remains. These spaces, they write, may reflect a rejection of “Indigenous autonomy and agency over their communities and their own Ancestors.”

But how do sellers explain the provenance of the remains they offer? Huffer and Graham analyze these “stock narratives” in detail, finding that most remains are described as former medical specimens. Buyers are thus invited to give new life to a dusty skeleton plucked from the corner of an old-fashioned doctor’s office. Additionally, sellers in the United States generally proclaim that the sale is entirely legal except in a handful of listed states.

It’s true that a substantial number of human remains from Kolkata, India, were processed into skeletons for medical schools around the world from the mid-1700s until a national ban on such exports in 1985. But they were not the informed, willing donors to medical research we might imagine; instead, these are often the remains of people sold by their desperately poor relatives. Huffer and Graham point out the ethical problems of prolonging the possession of the remains of people who were not “in any position of power to resist what happened to them.”

Modern medical collections were also stocked from even more ethically indefensible sources. Huffer and Graham discuss, for instance, scholarship on segregated cemeteries in the American South, where graverobbing to acquire medical specimens is visible in the archaeological record. They even quote from the memoirs of Griffith Evans, a White doctor who recalled that during his days at a Canadian medical school just before Emancipation in 1863, students worked on the remains of Black people who had been “packed in casks, and passed over the border as provisions, or flour.”

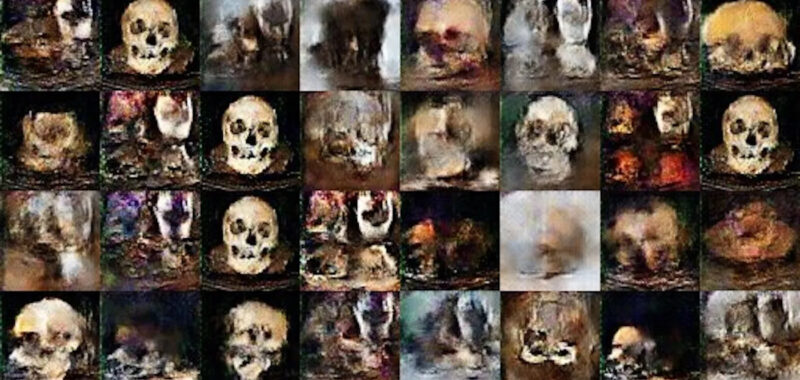

In other cases, the seller’s claim that a skeleton came from a medical collection might hide an even more disturbing truth. Huffer and Graham performed ancestry estimation on a sampling of images of skulls advertised for sale online. (Different populations have statistically similar measurements between “landmarks” on the skull; thus, scientists can use statistical comparison to estimate the probability that a skull comes from a certain population.) In only a quarter of the cases did their analysis strongly support what the vendors were claiming about the source of the skull. It is unlikely that any of the skulls they claimed to be European actually were. And in a quarter of the cases, the analysis suggested that the remains were those of Native Americans.

It was only in 1990 that the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) made it a felony to buy, sell, or otherwise profit from Native American human remains. No wonder sellers are not eager to describe the bones they sell as such. But the amount of misclassification uncovered by Huffer and Graham means no one should believe their breezy claims about legality.

The situation for non-Native remains is harder to summarize, since it depends on local laws. (Here’s a collection organized by state.) Nearly all these laws predate the existence of the internet; Huffer and Graham note that legislation “struggles to keep pace” with phenomena such as a skeletal guitar.

Yet in some jurisdictions, the law seems clear and captious enough to prohibit the trade. In New York, for instance, it is a misdemeanor to purchase a body or body part for any purpose other than burial. But the existence in Brooklyn of a commercial “museum” with a wall hung with spinal columns is just one of the signs that few prosecutors have prioritized applying existing law. Online sellers can continue to operate openly, trading tips about legal loopholes with one another and creating an impression among potential customers that the trade is perfectly legal.

Throughout These Were People Once, Huffer and Graham’s careful prose is as respectful of the living as the dead. Rather than excoriating buyers and sellers, they seek to understand their beliefs and motivations. The most vehement they get is when discussing the failure of scholars: “We write for each other, we publish behind paywalls, and in the absence of accessible (in every sense) writing, people turn to the material that is available.” Like pseudoarchaeology, the human remains trade arises in part when our wonder at the world is captured and twisted for profit.

Huffer and Graham urge their readers never to purchase human remains, to report their sellers to relevant authorities, and to fight the exoticizing tales woven about these remains by telling the hard stories about their likely origins. In the end, they want to change our understanding of what we see when a skull pops up on one of our feeds.

These Were People Once: The Online Trade in Human Remains and Why It Matters (2023) by Damien Huffer and Shawn Graham is published by Berghahn Books and available online and at independent booksellers.