LONDON — Spotlit in the dark historic vaults of Somerset House, Jo Pearl’s “Oddkin” (2024), a theater of delicate alien creatures that visualizes the microorganisms in healthy earth, is dramatically interwoven with its own shadows. Crafted from clay — fundamentally, a form of mud — Pearl’s work strives to help us overcome our widespread squeamishness about soil, particularly in cities, where we prefer it to be out of sight and out of mind. SOIL: The World at Our Feet attempts to bring the natural material back into view as something alive, essential, and crucially, vulnerable.

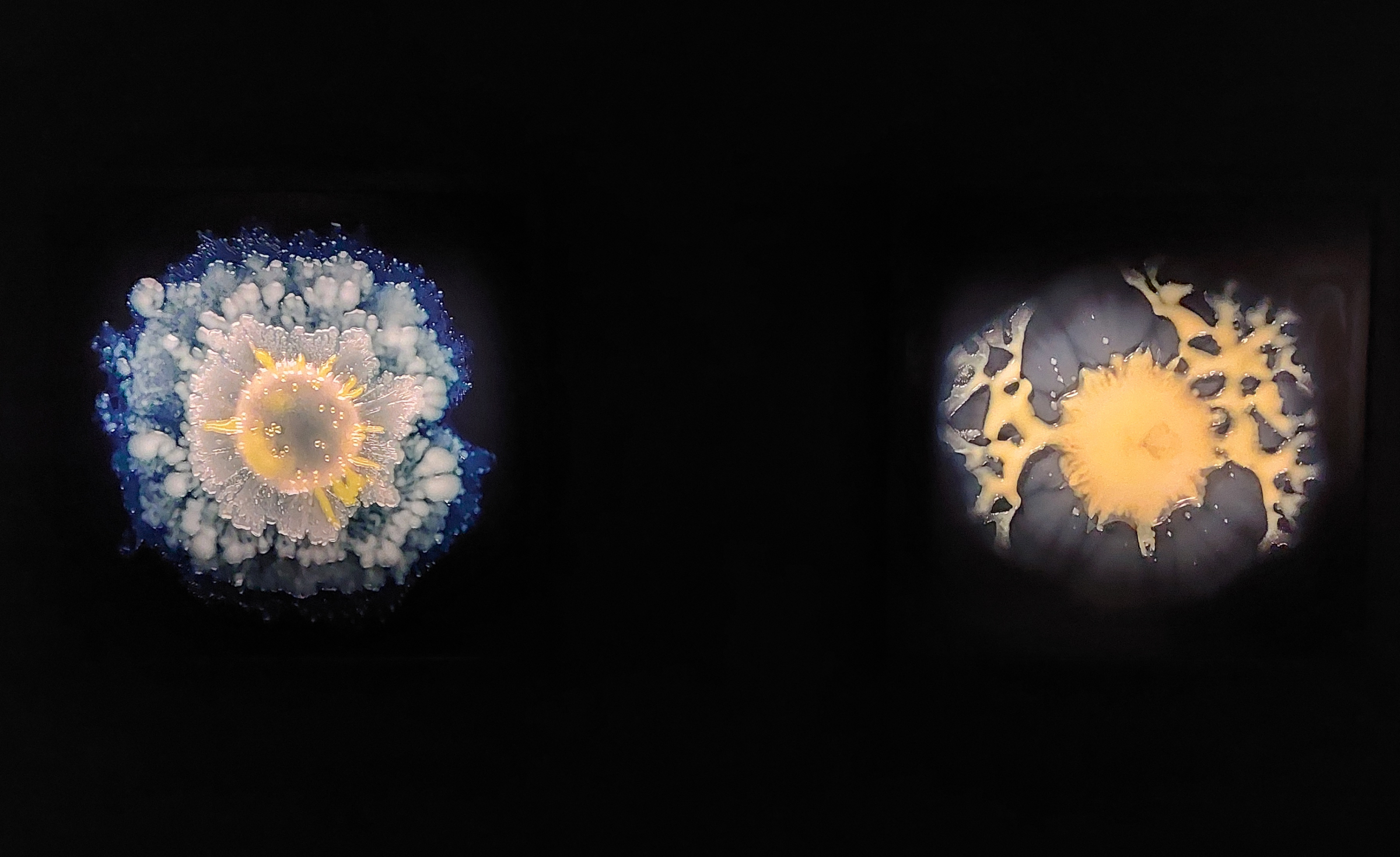

As Pearl’s installation suggests, soil is a highly complex mesh of plant matter, fungi, and bacteria working to recycle and regenerate the living earth. In this time of ecological precarity, it is no surprise that the complexities of earth itself offer fertile ground for artistic investigation and experimentation. In the exhibition, these range from Tim Cockerill and Elze Hesse’s flower-like digital photographs of bacteria, to Herman de Vries’s more analog grid of earth pigment samples, to Miranda Whall’s painstaking representation of data from a soil sensor network using tiny pinpricks in paper.

Other works explore the emotional and cultural associations of soil, which has long been a metaphor for home and heritage. “The Flowers Stand Silently Witnessing” (2024), for instance, is a moving film work by Greek-Palestinian artist Theo Panagopoulos utilizing archive footage of wildflowers in Palestine in the 1930s, suggesting an entanglement of people and land that is currently being erased. “I look at the past, unable to cope with the present,” the captions read, “But the archive can’t hold my grief.”

Elsewhere, Annalee Davis’s work exhorts viewers to “unlearn the plantation,” drawing upon her experiences of living and working on a former sugar plantation in Barbados, where the earth is inextricably tied to extractive colonial violence.

The exhibition hopes to drive home the idea that soil is becoming depleted on a worldwide scale: Industrial farming and erosion are stripping it of its nutrients and ecological complexity, and consequently, the variety and abundance of life it can support. One of the most compelling displays in the show pairs two understated pieces by David Nash and Mike Perry. For “Sod Swap” (1983), Nash dug up a circle of turf from a Welsh field, in which a botanist counted 27 plant species, and planted it in a London park, where they counted only 3. Forty years on, the effect is reversed, with 39 species in the urban grass and only four in the rural turf. Progressive horticultural practices have made London parks more biodiverse, while vast rural agricultural areas have lost variety through soil degradation, monoculture planting, and intensive livestock grazing. Perry therefore inverts Nash’s project in “Reverse Sod Swap” (2024), inserting turf from a London park into a Welsh field.

While these works are all important, by the time I reached the end of the exhibition, I felt there was a key omission — soil itself. The exhibition and its artworks are very clean, with soil often represented through abstract patterning, documentary photographs, or video screens. These are all legitimate artistic means of engagement with the topic, but there was a lack of opportunity to get your hands dirty — even in imagination. The visceral smell and feel of earth were disappointingly absent, in a way that is perhaps surprising considering that the lead curators are both gardeners. The wild unruliness of soil might be challenging for dirt-wary urban visitors — but it might also prompt a more urgent response.

SOIL: The World at Our Feet continues at Somerset House (Strand, London, United Kingdom) through April 13. The exhibition was curated by Henrietta Courtauld, Bridget Elworthy, May Rosenthal Sloan, and Claire Catterall.