On the afternoon of 18 March 2018 my family and I visited Book Soup in West Hollywood, CA. We had arrived in town earlier that day, having driven down from the Bay Area, and walked to the bookshop from our hotel. My wife and daughter, who was almost three at the time, went to the children’s section, while I browsed in Fiction, now pushing an empty UPPAbaby stroller.

The aisles were narrow, and on a couple of occasions I found myself maneuvering awkwardly past—awkward because of the stroller—a man who was darting around in no discernible fashion, looking for books, seemingly working from a list, pulling them from the shelves, quickly inspecting them, and then either putting them back or placing them in a handheld shopping basket. At one point he came swiftly around a corner and we almost collided, that is, he almost ran right into the UPPAbaby. “Sorry,” I said, somewhat embarrassed to be pushing the stroller in the store (should have set it aside somewhere), but the man good-naturedly told me it was all right and continued his manic browsing.

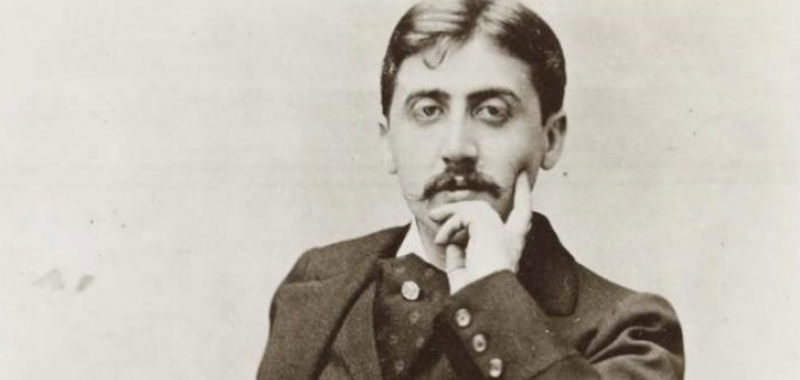

A few minutes he later he appeared next to me, mumbling to himself, running a finger along the book spines. I glanced over. He nodded amiably at me, still mumbling. There was something of the disheveled academic about him, bulky tweed coat, knit cap, beard. Then he disappeared again, and I browsed some more, making my selections: Trouble Boys, a biography of the Replacements, and Chateaubriand’s Memoirs from Beyond the Grave, a book I was curious about because I had heard it was similar to (or an influence on?) Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, which is my favorite novel ever.

In the children’s section, my wife was reading to our daughter. I parked the stroller and waited. At the nearby information desk, the manic browser had appeared, list in hand, speaking to a Book Soup employee, who was looking up titles for him on the computer. Hearing the man talk, a strange feeling came over me. That voice . . . Suddenly I knew who he was. It was so obvious, just take away the beard. But it was more than mere recognition. It went deeper.

My wife glanced up. I nodded at the information desk. She leaned over and looked. “That’s Judd Nelson,” I whispered.

Maybe he heard me. If so he did not acknowledge it—just kept chatting with the clerk. I knew this sort of thing must happen often in Book Soup. I also knew, after years of living in New York City, where I occasionally found myself in the presence of celebrities, that the thing to do was be cool, say nothing, do not indicate that you have seen the famous person, and whatever you do, do not approach. And I was happy, in that moment, overwhelmed by a whirl of sensations from my long-ago childhood, everything unleashed by the voice of the actor who played John Bender in The Breakfast Club, to adhere to that social contract. I did not stare at him, nor say another word about it.

My wife gathered the books she was going to purchase, took my selections, and she and my daughter went to pay while I took a last look around. I was heading for the exit, still pushing the stroller, when I glanced over and saw Judd Nelson waiting at the register. Through the glass door I could see my wife and daughter outside on Sunset Boulevard.

I looked back at Judd Nelson.

Judd Nelson was looking at me.

He smiled.

I waved.

Judd Nelson then gave me a friendly nod.

And I approached him.

“Are you Judd Nelson?” I asked.

A ridiculous question!—since my reaction, the very act of walking over, indicated I knew who he was. Briskly he nodded, said yeah, and with that out of the way I said, “You know, I recognized your voice back there”—again confirming there was no need to ask if it was him—”and it unleashed this”—here I paused, waving a hand for emphasis—”Proustian memory surge, my whole . . . childhood came rushing back and . . .”

My thoughts trailed off.

“I hope it was good,” he said.

Later I would realize he meant my childhood—Judd Nelson hoped my childhood was good. In the moment, however, nervous and embarrassed, I assumed he was referring to the aforementioned Proustian memory surge.

“Oh, it was great,” I said, looking him earnestly in the eyes.

I did not know what to say next.

The customer who had been at the register had left, and the clerk was ready, smiling expectantly, waiting to ring up Judd Nelson’s many purchases. Glancing at her it occurred to me how gauche she must find me, she who no doubt saw celebrities often and, no matter how excited she might have been, would never stoop as low as this. Would never have begun babbling about a Proustian memory surge.

Just then my daughter called into the store. “Papa!”

Judd Nelson nodded toward her. “New life,” he said.

“Do you have kids?” I asked.

“No, no,” he said, shaking his head, and then explained (to me and to the clerk, who now seemed a part of the interaction) that he had two sisters, one of whom had kids, thus satisfying his parents’ desire for grandchildren, as he and the other sister were childless.

“Ah,” I said.

“What’s your name?” he asked.

I told him. He extended a hand. We shook vigorously.

“It’s great meeting you,” Judd Nelson said.

Again we were looking each other dead in the eye. There were close friends with whom I had never engaged in this degree of eye contact.

“You too,” I said. “Bye.”

*

I first started to read In Search of Lost Time in the fall of 2003. I was 29, unemployed, had recently finished graduate school, was still traumatized by a frightening experience in the World Trade Center on 9/11 (and deeply in denial of that trauma), and had picked up, semi-randomly, a copy of Swann’s Way. In a dim sense I was aware that the novel was part of a vaster work that was considered “difficult,” and featured a scene where a guy dunked . . . something into a beverage and then remembered things. But I knew nothing else about the book.

Not long before, I had read Ulysses, and while I ended up loving it, I found it hard to access at first. I felt anxious every time I opened it. The book’s reputation as both the greatest and most challenging novel ever written had been drummed into me (and all of us) for years. I read with companion texts handy, pausing a ludicrous number of times to look up every abstruse reference, stray bit of a foreign language, stylistic shift, parallel to The Odyssey, Dublin landmark.That is no way to read a novel, in my opinion. Only after I stopped trying to understand the book, moved past the sheer awe I felt merely holding it, did I actually begin to enjoy the damn thing.

With Swann’s Way, I experienced no such anticipatory anxiety. From the first, terse sentence, “For a long time I would go to bed early” (in C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin’sModern Library translation)—whose brevity, I would shortly discover, was uncharacteristic—I was hooked.

Proust’s lush prose enveloped me like warm water. I could see everything he was describing—relate to everything he was describing: the Narrator, alone, drifting in and out of consciousness, dreamily recalling, in “confused gusts of memory,” other bedrooms he had slept in, in other houses, other towns; the “old days at Combray,” where his “bedroom became the fixed point on which [his] melancholy and anxious thoughts were centered.”

Anxiety. Melancholy. Memory. Meditations on childhood. Those were catnip to me then, as indeed they are now. And all of this comes before the Narrator has a highly consequential cup of tea (the scene is on page 60 of my edition), a spoonful of which contains a soaked piece of petite madeleine and ushers in not merely a fleeting late-night remembrance but an entire vanished world populated by dozens of characters among whom the Narrator moves through time on his slow journey from society figure to his long-deferred calling to be a writer.

I devoured Swann’s Way and volume two, Within a Budding Grove (the Penguin edition, translated by James Grieve, has the more literal—and better—title: In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower), at once savoring the long sentences, long paragraphs, the many philosophical digressions, and swiftly turning pages. I have read whole thrillers marketed as pulse-pounding that did not excite me as much as, say, Charles Swann’s reaction to composer Vinteuil’s “little phrase,” or the Narrator’s descriptions of the sea and the surrounding landscapes at Balbec.

And I am convinced that no writer in any language is as devastatingly accurate as Proust on the subject of obsessive love. We see it with Swann and Odette, the Narrator and Gilberte, and later (and most exhaustively, indeed maddeningly) the Narrator and Albertine. It is all there: longing from afar, the thrill of the chase, euphoria of the conquest, followed—in some cases almost instantly—by a deadening of feeling as sky-high expectations are not met, or a toxic jealousy emerges, or habit and routine (as happens throughout the novel, in all aspects of life) simply do their slow-drip work, grinding down even the most thrilling contingencies.

At that time in my life, my late twenties, spiraling in a pattern of fixating on inaccessible love interests, convinced that only their affection could save me, only to remain emotionally unavailable myself, it was as if the Narrator was holding a mirror before me that reflected only my most embarrassing or shameful selves.

Things slowed considerably in the third book, The Guermantes Way. This is when the Narrator, now a young man (as far as I know, his age is never explicitly stated), enters Parisian high society. Two long set pieces—an afternoon soiree and a dinner party—consume hundreds of pages and feature a dizzying number of characters, name upon name, cousins and second cousins, uncles, aunts, spouses, many of whose histories and personal qualities are relayed at length.

These gatherings also allow the Narrator, sometimes with interlocutors, sometimes in inner monologues, to ruminate on visual art, music, fashion, literature, architecture; the interpersonal relationships, behaviors, and nomenclature of the nobility; and—the most pressing political matter of the day—the Dreyfus Affair.

In my enthusiasm for the first two books I had rushed out to buy all of the others (something I often do with series, whether In Search of Lost Time or John Sandford’s Prey novels). I now had the complete 2003 Modern Library edition, whose spines together formed a picture of a fancy collar. But I needed a break. The long party scenes had taxed me. The accrual of detail was stunning, but after the dreamy seaside atmosphere of Within a Budding Grove, where the Narrator first encounters Albertine and her “little band” of friends, the crowded drawing rooms of the aristocracy felt stifling indeed.

I figured I would read something lighter, a thriller of two, then take up the Search again with the fourth volume, Sodom and Gomorrah. Instead I stayed away for 10 years.

*

I stepped out onto Sunset Boulevard with the UPPAbaby. My daughter walked over and, blood still buzzing, feeling both excited and deeply embarrassed, believing I had said absurd things to Judd Nelson and should not have approached him after all, I buckled her into the stroller. No sooner had I done so than a woman stopped and began fawning over her. “Oh look at her!” the woman said, “you can see it in her eyes, how smart she is, how present!”

The woman looked to be in her mid-sixties, or maybe around 70. She had long white hair and was dressed fashionably, wearing expensive-looking leather boots and walking a small dog. My daughter, who is very social, was staring at her happily as the woman then told us that she considered herself a “universal mother,” and so she was our daughter’s mother, and mine and my wife’s too. Still disoriented by my encounter with Judd Nelson, I could say nothing, nor was my wife, frazzled by this woman’s sudden attentions, able do more than smile politely. The woman leaned over and spoke loudly—almost yelling—into my daughter’s upturned face. “You are so, so special! Don’t ever forget it!”

We then walked on, along Sunset, no destination in mind, as I told my wife about my interaction with Judd Nelson, still vacillating wildly between exhilaration and mortification. A moment later we were by the Viper Room, and past and present continued to collide as I pushed my daughter over the spot on the pavement where River Phoenix had collapsed and died 25 years earlier, an event which had devastated me at 19, loving the actor as I did, and stunned and saddened my generation in ways that I believed would echo through time.

Back then I had thought River Phoenix would be our James Dean, that his legend would only grow, that he would become an icon adored by future generations (I myself drove to Fairmount, Indiana, and genuflected at James Dean’s grave 40 years after the actor’s death), subject of disappointing biopics, his beautiful, haunted face staring out from t-shirts, posters, commemorative plates, album art. Instead he seems to have been largely forgotten, which is all the more curious given his brother’s current fame. And maybe this is apt, given that my generation, Generation X, has also, for all practical purposes—and I see this now more clearly than ever—been forgotten . The Baby Boomers hung in there, they would not step aside as earlier generations had, and the next thing I knew I was being asked to sympathize with the young people who had come up behind me, whose grievance was similar in a way—to crudely generalize: Boomers, in their titanic self-regard, screwed us over—but whose attitude was markedly less caustic, in fact nearly irony-free.

As for Generation X, we drifted uneasily into middle age. At a farmers market with my family once, I complimented a teenager on her Pyromania t-shirt, thinking we might share a word or two about that masterpiece. Instead, she flashed a sort of thumb half-up gesture and brushed by us without even breaking stride.

*

Early in 2014 I was living in Knoxville, TN. I was 39, married, and (with the aid of a therapist) trying to stay open to the idea of maybe becoming a father in the near future. And—in a grim harbinger of what I would likely be able to contribute financially to a growing family—working part-time in a bookstore.

The shop featured a small selection of used books among which I noticed, one slow afternoon, the Lydia Davis translation of Swann’s Way. I picked it up looking to kill a few minutes, read the introduction, then flipped to the first page. For a long time, I went to bed early.

I was hooked again, and bought the book (my third copy), knowing this time I would not stop the Search until I had reached the end. To ensure this, I imposed the system I had used when reading Samuel Beckett’s Trilogy: 10 pages first thing every weekday morning, and 20 on weekends. As before, I found the first two books sublime. I was now reading the Penguin version, each volume done by a different translator, and true to form, bought the whole series, only four of which were available in the U.S. at that time. With some apprehension, I started The Guermantes Way, recalling those interminable salons.

Only this time I liked them! Proust is an extremely skilled mimic, and I relished his character work, the way he breathes individual life into a sweeping array of personalities: how they speak and gesture; a covert glance; sycophantic laughter; a sudden, sarcastic tirade; an abrupt dismissal followed by an embarrassed blush. And while everyone seems to adore the neurasthenic Narrator’s company, even to covet it, he is never the hero, exactly. At one point a character dashes the Narrator’s hope of one day becoming a writer:

“‘Are you busy writing something at the moment?’ M. de Norpois asked me . . . ‘You once showed me a rather overwritten little piece, a bit too finicky in manner. I gave you my frank opinion: what you had done was not worth the paper it was written on . . .’”

In Sodom and Gomorrah, the Narrator is so afraid that his invitation to the Princesse de Guermantes’ exclusive party is a hoax that he gives the doorman (“clad in black like an executioner”) his name “as mechanically as a condemned man allowing himself to be attached to the block.” In fact the invitation is real, and after briefly greeting his imposing hostess, he “did not dare approach her again, sensing that she had absolutely nothing to say to me.”

The days and the weeks and the months passed. I established a lovely groove with the novel, came to relish my mornings with it, drinking coffee as I navigated the long sentences, the sometimes pages-long paragraphs, unwilling—almost unable—to move on with the day until I had completed my 10 (or 20) pages.

Not all was rapturous: The Prisoner could be a drag, the Narrator’s obsession with Albertine, in particular the question of whether she is a lesbian, tipping over into pathology. (On the other hand, the novel also features Baron de Charlus’s dramatic break with domineering social climbers the Verdurins.) But I read on, taking frequent small sips of that ocean of prose. The Fugitive was also uneven, its continuation of the obsessive-loop Albertine narrative giving way to a showstopping description of the Narrator reading his first published article—which initially he is unable to recognize as his own!—that left me absolutely giddy.

“When I wrote them,” he reflects on seeing the published piece, echoing sentiments I have experienced countless times, including during the writing of this very essay, “the sentences of my article were so weak compared to my thought, so complicated and opaque compared to my harmonious and transparent vision, so full of gaps which I had not managed to fill, that reading them caused me to suffer, they had only accentuated my feelings of impotence and an incurable lack of talent.”

Separated by a century, and vast geographical and cultural distances, Proust’s and my biographies could scarcely be more different. He was a doctor’s son, bourgeois, sickly, raised in privilege in one of the world’s great cities, and even as a young person possessed of stunning erudition. I grew up in rural Michigan, in a working-class household in the 1980s, a latch-key kid raised on a steady diet of MTV, late-night HBO, and Burger King. Yet very often, when reading In Search of Lost Time, I set the novel aside, stunned—even a little uncomfortable, sometimes—thinking: Holy shit, that’s me.

I returned to the novel recently, a decade after last reading it. Once again I had picked up Swann’s Way in an idle moment, intending only to read a few passages . . . and could not stop. I found myself drawn back to whatever volume I happened to be on throughout the day, and pushed my daily page count to 20.

I live in California now. Today I turned 50. A few months ago my daughter turned nine. She had a sleepover birthday party, and my wife and I watched as she and five friends danced madly in the living room to Taylor Swift. It’s going too fast, I thought, recalling the days when she could do little more than lie on a playmat and reach ineffectually for the tail of the plush monkey that hung over her.

Shortly before her birthday, I had finished Finding Time Again, the novel’s concluding volume, in whose final sequence, the bal de têtes, many of the characters we have been reading about appear, their faces and bodies irrevocably, at times grotesquely, altered by age. By Time.

The Narrator isn’t spared either. “I could see myself,” he writes, “as though in the first truthful glass I had ever encountered, reflected in the eyes of old men, who in their opinion were still young, just as I was in mine, and who when I described myself as an old man, hoping to hear a denial, showed in the way they looked at me, seeing me not as they saw themselves but as I saw them, no glimmer of protestation.”

Holy shit, that’s me.

*

But here is one of the strangest things about that afternoon in West Hollywood, when I nervously babbled the words Proustian memory surge while speaking to Judd Nelson, who played John Bender in The Breakfast Club, a movie I have seen countless times and whose imagery, dialogue, and music do in fact conjure a vertiginous swirl of memories, vanished years, whole eras of my late childhood and adolescence, even my young adulthood. (I remember seeing it at the run-down Eastowne 5 in the summer of 1996, when I was 22, threads and specks flickering through the old print of the film.) Minutes after my encounter with the actor, and after passing the Viper Room and the corner where River Phoenix died, my wife and daughter and I crossed Sunset Boulevard, and my wife entered a liquor store to buy a bottle of wine to bring back to the hotel, and rushed out a moment later, saying, “You’ll never guess what song is playing in there!” What? It was Simple Minds singing the theme from The Breakfast Club, “Don’t You (Forget About Me).”