When you buy through links on our articles, Future and its syndication partners may earn a commission.

Astronomers often have more questions than answers about the universe — and the universe, in turn, has asked its own question. Quite literally.

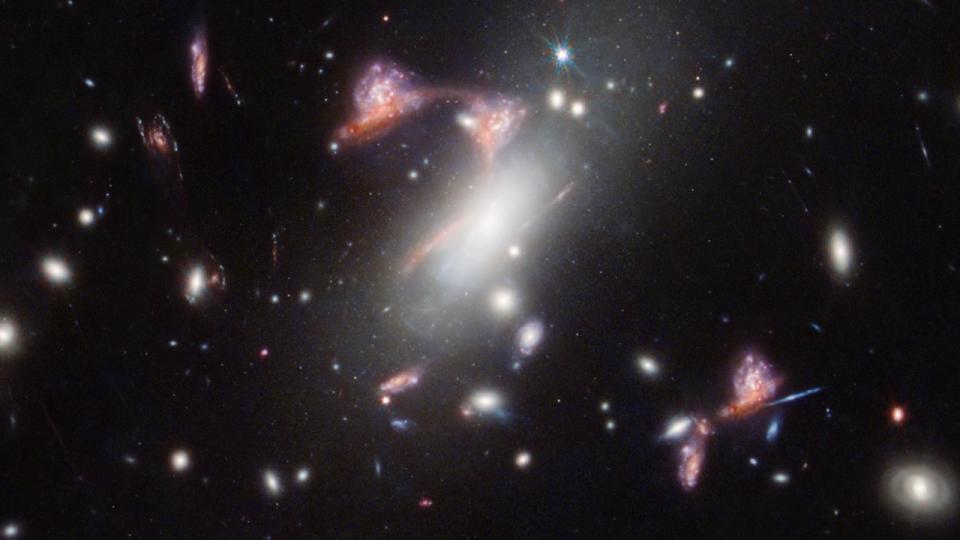

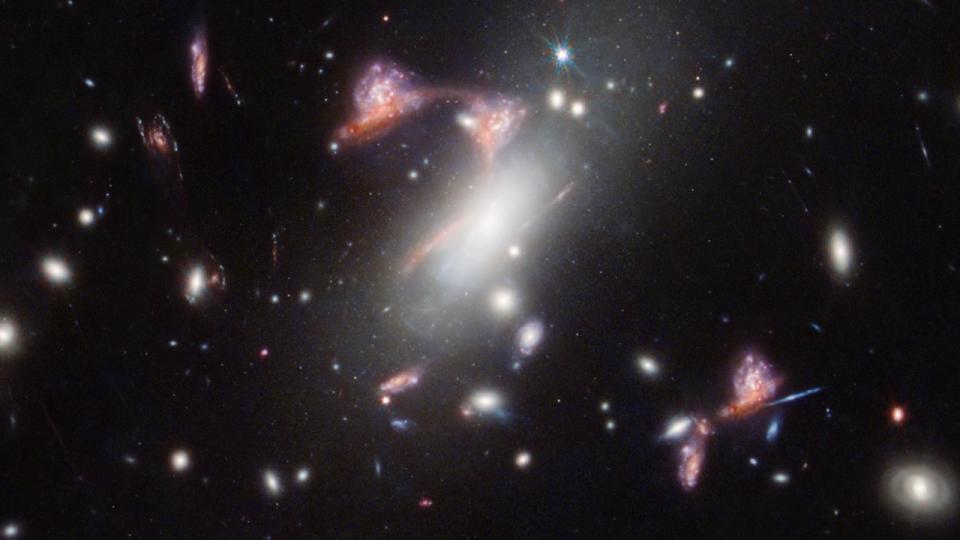

Last year, the James Webb Space Telescope fortuitously spotted the unmistakable shape of a question mark across the sky. The uncanny feature was captured lurking at the bottom of an image of a pair of forming stars in the Vela constellation roughly 1,470 light-years from Earth. The picture soon went viral on social media sites, prompting a myriad of guesses of its nature, from a sign of aliens trolling us to a glitch in the Matrix.

The JWST’s best look yet at the so-called “Question Mark Pair” released Wednesday (Sept. 4) has finally revealed some clues about the cosmic riddle — and sorry, it’s not aliens.

Astronomers already knew from the object’s red color that it was quite distant, and posited the shape of the question mark was traced by a pair of faraway galaxies spiraling toward each other in deep space.

Related: Is the James Webb Space Telescope really ‘breaking’ cosmology?

The latest image concurs, revealing in detail the two interacting galaxies — a red, dusty galaxy that marks the curve of the question mark and a white spiral galaxy seen hugging the looping arc to its right. The question mark’s dot is an unrelated galaxy serendipitously present in the right place from the JWST’s view. The image also features thousands of disparate light streaks, so, if you squint, you’ll probably find some apostrophes, colons, semicolons and other punctuation marks, too.

Data from the JWST shows the two galaxies are 7 billion light-years from Earth and close enough to be interacting with one another. Possibly as a result of their gas reservoirs colliding, both galaxies are actively forming stars in several compact regions, astronomers say.

“However, neither galaxy’s shape appears too disrupted, so we are probably seeing the beginning of their interaction with each other,” Vicente Estrada-Carpenter of Saint Mary’s University in Nova Scotia, who led a study on the galaxy pair, said in a recent statement.

His entire team was stunned when the telescope’s data was processed and turned into color images, he told The Washington Post. “We instantly all saw the question mark,” he said. “It’s just a beautiful image.”

The two prominent galaxies are distorted and duplicated by a foreground galaxy cluster that’s so massive it warps the fabric of spacetime, creating something like a cosmic funhouse mirror. This quirk of our universe is called gravitational lensing, and because of it, one of the two question-mark galaxies — the red one forming the top of the symbol — appears five times in the image. In fact, the kind of “multi-mirrored” gravitational lensing we see in the JWST’s new image is a rarity because it demands a remarkably precise alignment between the observer, distant galaxies and the lensing object, which in this case is the galaxy cluster MACS-J0417.5-1154. This particular type of lensing is known to astronomers as a “hyperbolic umbilic gravitational lens.”

So far, only a handful of similar multi-mirrored galaxy configurations have been observed, astronomer and study co-author Guillaume Desprez of Saint Mary’s University said in the statement. “It demonstrates the power of Webb and suggests maybe now we will find more of these.”

Related Stories:

— Early galaxies weren’t mystifyingly massive after all, James Webb Space Telescope finds

— Listen to the eerie sounds of an exploded star in new NASA video

— James Webb Space Telescope strikes again, delivers new shining galaxy image

By studying the star forming regions seen in the JWST’s latest image, astronomers can infer how galaxies evolved over the history of our universe. Meanwhile, the telescope’s snapshot is also shedding more light on the past of our own home galaxy, the Milky Way.

The masses of the two interacting galaxies are similar to our galaxy’s mass billions of years ago, so “Webb is allowing us to study what the teenage years of our own galaxy would have been like,” study co-author Marcin Sawicki of Saint Mary’s University said in the statement.