[ad_1]

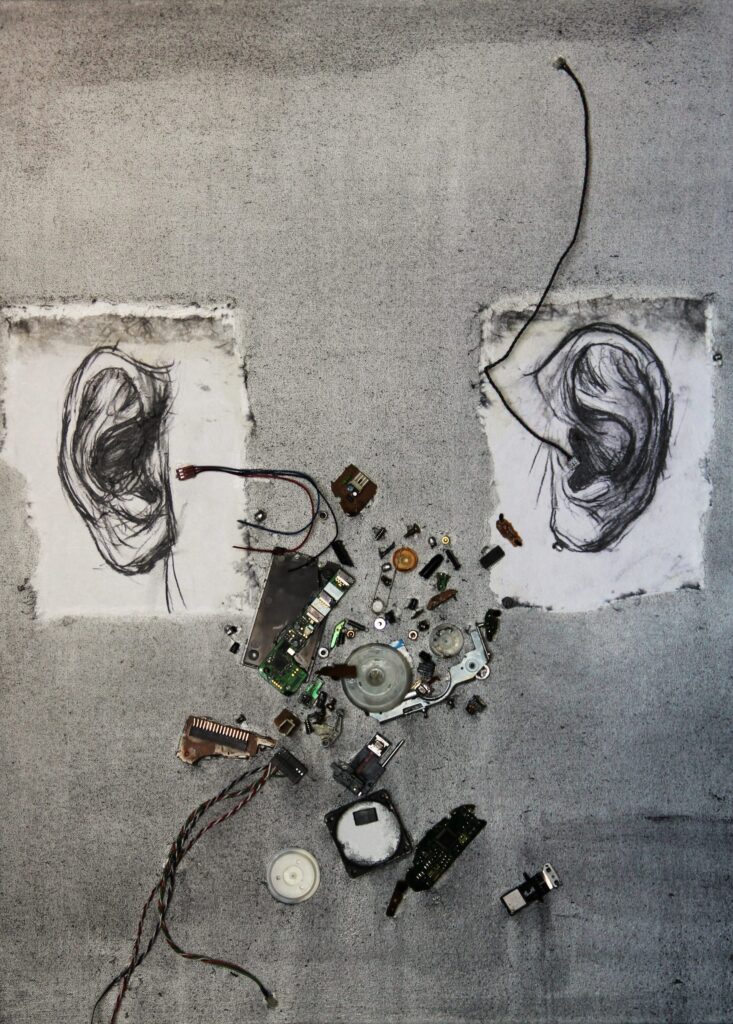

CULVER CITY, California — Counter/Surveillance: Control, Privacy, Agency, a year-long new exhibition at the Wende Museum in Culver City, brings together archival artifacts, including surveillance devices; spy cams; early facial recognition technology; manuals; and documentation of methods used by the Stasi, the East German secret police agency, and the KGB, the Soviet intelligence agency, to search for dissidents and spies. These materials are cleverly interspersed among a dozen or so contemporary artworks, cumulatively forming an interrogation into our modern-day surveillance society. True activism, the exhibition reminds us, lies in watching the watchers.

The contemporary artworks featured in the exhibition include German artist Verena Kyselka’s “Pigs Like Pigments” (2007), which incorporates printouts of the files the Stasi kept on her, overlaid in red with personal details about her uneventful daily life during the oppressive totalitarian regime. Other artwork includes mixed-media prints by Sadie Barnette, who adds floral decorations to enlarged and reproduced assets from the 500-page file the Federal Bureau of Investigations kept on her father, who founded the Black Panther Party’s local Compton chapter. And in the film The Making of Dragonfly Eyes (2017), Xu Bing uses publicly available closed-circuit television footage to piece together a fictional narrative about a woman who leaves the spiritual safety of the Buddhist temple she calls home and is forced to learn how to exist in modern-day China, with its 700 million surveillance cameras. Xu’s work makes us question reality and our interpretation of it.

The archival materials, about 75% of which are borrowed from archives from all over the world, are so extensive that it may take several visits to the exhibition to take in their full breadth and scale. For instance, one could easily miss the smelling jar, which was used by the Stasi to train dogs on the scents of dissenters. Great lengths were taken to acquire the smells, including raiding dissident apartments and stealing underwear. On the counter-surveillance side is a display of American musician Merryl Goldberg’s sheet music, concealing within its musical notes a secret language that was used to record the addresses of political dissidents — a creative method that remained undetected by Soviet police, allowing Goldberg and her bandmates the chance to share the encoded stories in the United States.

The exhibition feels particularly important today, in a time of hyper-surveillance, from programmatic digital ads that follow our every move online, to voice detection on our phones that feed us more ads, to geo-location devices in our cars, to CCTV cameras on our sidewalks, to dark web sites that sell our personal information, to hackers breaching another database compromising our passwords and leading to possible identity theft, to Artificial Intelligence technology that can mimic our voices and plant our faces on someone else’s body. The list is seemingly endless. Some could argue that certain methods of modern-day surveillance might be necessary, say, accessing a school shooter’s phone and prosecuting him. And yet it’s impossible not to ask ourselves, has it all gone too far?

Counter/Surveillance: Control, Privacy, Agency continues at The Wende (10808 Culver Boulevard, Culver City, California) through October 19, 2025. The exhibition was organized by the museum.

[ad_2]

Source link