Approaching Japan’s artistically diverse and politically entangled history of art is a formidable task, not least because English-language art history publications on the multifaceted subject are few and far between. The new scholarly yet accessible book The Splendour of Modernity: Japanese Arts of the Meiji Era sets the record straight with remarkable clarity.

Author and curator Rosina Buckland’s book joins a steadily growing number of titles dispelling the whitewashed argument that Japanese art of the historical Meiji era of 1868 to 1912 resulted from foreign influences that watered down local art forms, thus, stripping them of their “Japanese-ness.” Instead, Buckland posits that art during the Meiji period developed gradually and combined characteristic Japanese styles with foreign ones, such as Impressionism, new techniques of printmaking, oil painting, and realism. In doing so, Japanese genres honed existing traditions and welcomed fresh perspectives.

The Meiji Restoration marked the overthrow of the country’s 700-year-old shogunate military dictatorship. The new government extended its modern vision to the production of arts, establishing Japanese museums and a presence in the international art scene, such as expositions in Vienna (1873) and Philadelphia (1876). The five chapters of this vibrantly illustrated book present these distinctive artistic developments — decade-wise, blossoming in cities like Tokyo and Kyoto. The author also provides a teachable introduction with a commentary on the published historiography of Meiji-era arts and a political summary.

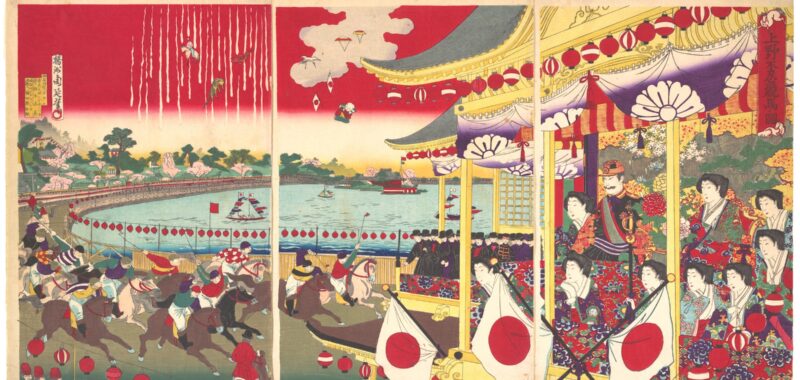

In the early years of the Meiji era, Buckland explains, Japanese artists created first-rate scrolls and peerless cloisonné enamelwork. They also continued meeting local and tourist demands for woodblock or ukiyo-e prints evolving from the preceding Edo period from 1603 to 1868. As Japanese crafts excelled in foreign press, the government created new policies to aid craftspeople, while Impressionist techniques and drawing in the manner of Western figurative styles garnered prominence in the country.

A major strength of the book lies in Buckland’s detailed research and nuanced argumentation, emphasizing currents of nationalism and evolving individualism in Japanese art between 1885 and 1905. Artists including ukiyo-e printmaker Adachi Ginkō considered art a token of national prestige, often rendering political events on imperial premises. For instance, in the woodblock print “View of the Issuance of the Constitution in the State Chamber of the New Imperial Palace” (1889), Ginkō forefronts the emperor clad in Western military dress, accompanied by his family and members of the government, inside a partially traditional Japanese interior. Over the next few years, several other Japanese artists were inspired by the technical possibilities of printmaking, as globalization brought them closer to the works of artists like Edvard Munch and William Nicholson. Yamamoto Kanae created prints like “Fisherman” (1906) bolstering new methods and centering working-class people.

The Splendour of Modernity arrives at an opportune time, as academics strive to “decolonize” art history curricula. Buckland critiques dominating Western approaches to Japanese art, writing that it’s often “criticized as either now too modern or still not modern enough.” Fittingly, she argues that modernism in late-1800s Japan should not always refer to the Western paradigm, as Japanese modernity takes equal stimulus from East Asian countries such as Korea and China. An abundance of artistic strands, ranging from traditional Japanese and ancient Asian styles to Western trends, is precisely why Meiji-era art resists any reductive categorization.

The Splendour of Modernity: Japanese Arts of the Meiji Era (2024) by Rosina Buckland is published by Reaktion Books and available online and through independent booksellers.