SANTA BARBARA, California — Is it possible to define California’s aesthetic language? As a home to almost 40 million people, its artistic chatter takes on thousands of different tones. There’s the tongue-and-cheek wordplay from canonical greats like John Baldessari, odes to peace by the artsy nun Sister Corita Kent, and carefully reproduced graffiti by Afonso Gonzalez Jr., whose artistic sensibilities were in turn influenced by his father’s career as a sign painter.

Instead of narrowing down California to just one language, curator Alex Lukas makes room for many dialects in his exhibition Public Texts: A Californian Visual Language, which is currently on view at the Art, Design & Architecture Museum at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The exhibition shows how artists use text and image to play up different aspects of Californian culture.

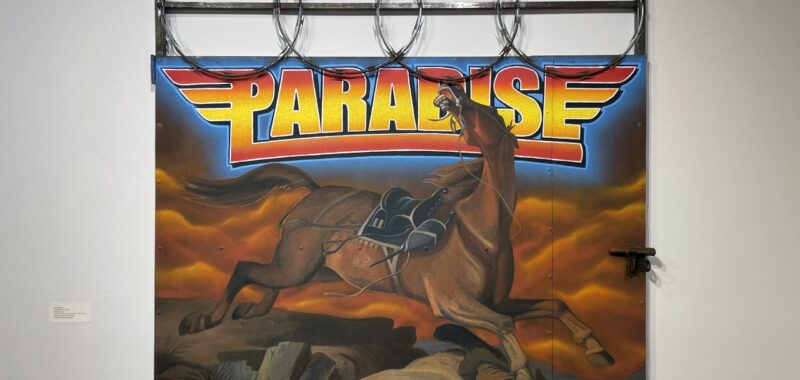

One way Southern California is represented is through airbrushed lettering, typically associated with lowriders and auto shops, which Ozzie Juarez captures in “Paradise” (2024). The word pops off behind an expertly rendered painting of a horse, which has been applied to an oxidized gate and adorned with rolls of barbed wire. Northern California is captured through the display of various issues of the Black Panther Newspaper (1967–80), in which Emory Douglas illustrated political cartoons and visualized acts of protests through solid colors, thick black lines, and halftones.

The historical works show that California has been a silkscreen and sign-painting hotspot since the mid-20th century. There’s a vitrine dedicated to the Colby Poster Company, which advertised bachata dance nights and underground raves on fluorescent gradient backgrounds. Lukas juxtaposes these pieces with contemporary works that adopt these techniques. Eve Fowler’s “This Always comes to That” (2011–12), for instance, pops off a red, yellow, and green Colby gradient.

California’s language is also mundane. In “Injured?: I” (2024), Gonzalez Jr. uses oil paint to reproduce the phone numbers and portraits of the spokespeople from Los Angeles’s ubiquitous insurance billboards. Glen Rubsamen turns to strip malls, depicting a glowing “Food 4 Less” sign among a smoggy sky in “Sorry, Wrong Number” (2023). Streaks of orange vibrate just underneath the surface, giving the painting a smoldering effect.

Public Texts is not just a showcase of 2D works, however. It demonstrates that sculpture can also be a text-based medium through Georgina Treviño’s piece, “Siéntese Señora” (2024). She reworks the titular phrase into the tight, pointed angles of a blackletter font in a sculpture that recalls both a bench and a nameplate necklace, a common fashion accessory in Chicana culture. The legs form chains, which curl along a white plinth, eventually connecting through a clasp.

As the exhibition progresses, the size of its works grows. In the second gallery, Ana Teresa Fernández’s work “SHHH” (2023), made up of hundreds of small acrylic mirrors, casts reflections like a disco ball. Whereas the exhibition began nearly empty, this part of the show includes a collection of risograph buttons and shelving that holds skewed texts on bright orange paper. These are class projects that students at the college made using the exhibition as inspiration. Their inclusion is a clever way of tying in a new generation into the show’s thesis — and a foreshadowing of an emergent new slang in art and language.

Public Texts: A Californian Visual Language continues at the Art, Design & Architecture Museum at the University of California, Santa Barbara (552 University Road, Santa Barbara, California) through April 27. The exhibition was curated by Alex Lukas.